9–12 minute read

You can increase drought tolerance and minimize disease by watering, fertilizing, and mowing correctly.

basic principles

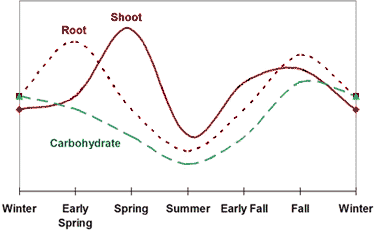

Water and fertilizer should be timed to periods of root growth, not blade growth. For cool-season grasses, root growth begins before blade growth in spring and after blade growth in fall. This is because blade growth is regulated by air temperature, while root growth is regulated by soil temperature.

modified from VA Extension “Spring” Into Your Turf: Fertility Programs

modified from VA Extension “Spring” Into Your Turf: Fertility Programs

Optimal root growth occurs when soil temperatures are 50–65°F, but growth occurs as long as the soil is not frozen and the temperature in the top inch of soil is below 75°F. Roots close to the surface die back when soil temperatures reach 90°F.

Optimal shoot growth occurs when daytime air temperatures are 60–75°F and nighttime air temperatures are in the mid 50s. Growth is minimal when air temperatures are below 50°F or above 80°F.

At 75°F and above, photosynthesis (energy production) declines and respiration (energy consumption) increases, resulting in an energy imbalance and the potential for starvation, especially at low mowing heights. Grass can will thrive only if reserve carbohydrates are present. Once reserves are gone, the grass will lose tissue it can no longer support, usually beginning with roots.

When to fertilize

Grasses in Orange County must endure heat, cold and drought. To cope, they need maximal root systems and carbohydrate stores. Because the goal is to maximize carbohydrate storage, apply 75% of the yearly nitrogen in the fall.

- ¼ yearly nitrogen at the beginning of root growth in spring:

Valentine’s Day - ¾ yearly nitrogen during root growth in fall:

Labor Day (beginning of blade growth)

Thanksgiving (best, after peak of blade growth)

When to irrigate

- Taper off starting in mid-April.

- Increase beginning in September.

irrigation

Follow these guidelines if you plan to keep your lawn green during the summer. Be sure to water consistently throughout the growing season, because your lawn can be permanently damaged if watering is begun and then discontinued.

Water infrequently to create deep roots. Most lawns receive twice the water needed for good health. A little stress encourages deep roots, so don’t water until you see signs of moisture stress. However, once signs of stress appear, water promptly to prevent permanent damage. Signs of water stress:

- First, footprints remain after walking.

- Next, wilting occurs. Initial signs of wilting occur in the heat of the afternoon. Blades acquire a dark bluish-gray color or folded or curled leaves (this helps to conserve moisture). The leaf blades will appear much thinner.

- Turf must be watered within 24–48 hours of the first sign of wilting to prevent serious injury. Apply 1 inch of water as rapidly as possible without runoff.

Water thoroughly, to a depth of 4–6 inches (you can probe with a screwdriver to determine moisture depth). For heavy, fine-textured soils, this is about 1 inch of water. Measure water distribution by placing shallow containers, such as pet food or tuna cans, around your lawn. Clay soils and slopes usually absorb no more than ¼–½ inch of water per hour. Allow time for the water to be absorbed (about 30 minutes), then water again until the desired moisture depth is attained. To save water and reduce runoff, position sprinklers and automatic irrigation systems so that the water falls on the lawn and not paved surfaces.

The ideal time is 4–7am, when grass is already wet from dew. Watering between 10pm–8am is less desirable, but still OK. Watering at the ideal time avoids creating additional periods of prolonged blade wetness, which can stimulate disease. It minimizes evaporative loss because this is usually the coolest, most humid, and least windy time of day. For convenience, use a simple water timer from any home and garden center.

Summer dormancy

Dormancy is the natural state for cool-season turfgrasses, such as fescues and bluegrass, when both soil and air are warm. Root growth stops before blade growth. Dormancy permits survival for up to 5–8 weeks without irrigation or precipitation. Your lawn will turn brown, but it is not dead. Grass species, lawn age, weather, maintenance practices, and soil influence recovery. In our area, fescue lawns usually require annual reseeding in the fall in order to remain dense. In Orange County, the dormant periods for cool-season turfgrass roots and blades are:

| Grass Part | Dormancy |

|---|---|

| Root Blade | Jun 01 — Sep 01 Jun 15 — Aug 15 |

Full lawn recovery occurs only under ideal conditions:

- no regular traffic

- moderate temperatures

- no shade

- minimal thatch

- good, uncompacted soil

Survival is adversely affected by poor maintenance practices such as low mowing and/or scalping, too much nitrogen fertilizer in spring and not enough nitrogen in fall. Survivial is also compromised by high night temperatures (mid-70s and above), which rapidly deplete stored energy reserves

Irrigation to prepare for dormancy

Irrigation should mimic root growth, so water as needed both before and during ‘green-up’ in spring. Note that when turfgrass crowns emerge from winter dormancy, the soft blades are especially susceptible to dehydration. Starting about mid-April, encourage dormancy by gradually reducing watering frequency.

maintenance of dormant turf

- Stay off the turf. Limit traffic (including mowing) to minimize crushing the turfgrass leaves and crowns.

- Water ¼–½ inch once every 2–3 weeks. This keeps turf crowns hydrated. The goal is not green turf, but increased long-term survival. Note that extended periods (usually longer than a week or two) of sunny, dry conditions with temperatures above 90°F can permanently injure even the best-conditioned lawn. If older advice suggested that no watering was needed, times have changed — fine-leaved fescues, perennial ryegrass, and some of the newer, improved varieties of Kentucky bluegrass do not go truly dormant like the older Kentucky bluegrass varieties. Instead, they grow very slowly under dry conditions. Lawns containing any of these grasses require irrigation every 2–3 weeks to stay alive through hot, dry periods.

- Don’t apply herbicides. Herbicides are ineffective on drought-stressed weeds but will damage drought-stressed turf.

- Be prepared to pamper recovering turf. Turf should recover 1–2 weeks after significant rainfall returns. Aggressive fertilization will usually be needed, as well as overseeding in the fall.

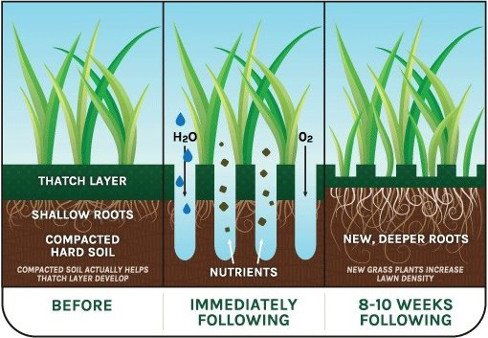

Aeration

Aerate (core) your lawn in the fall to let air & water reach the roots. In addition, the soil cores, if left on the surface, will mix with and help to break down thatch. Fall aeration is preferred over spring both because the holes will not be exposed to excessively hot temperatures and because any weed seeds that are exposed with the cores are less likely to compete with your grass.

Balancing shoot and root

Don’t stimulate shoot growth at the expense of roots.

Fertilizing

The best times to fertilize are roughly Labor Day, Thanksgiving, and Valentine’s Day. Don’t apply nitrogen in the months Feb-Aug. Late fall fertilization is advantageous because shoot growth has slowed but root growth is still active. Fall nitrogen applications greatly enhance the production of carbohydrates, which are stored for use the following growing season.

Don’t overapply nitrogen. Excessive spring fertilization reduces carbohydrate reserves and root development by stimulating rapid shoot growth. Shoot growth takes priority over roots for carbohydrate utilization. Follow the NCDA recommendations for potassium which promotes drought resistance.

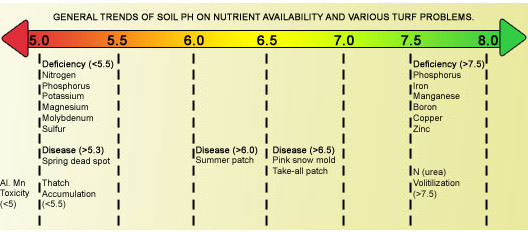

Keep the pH between 6 & 7.

Mowing

Ideally you should mow at the highest setting that is recommended for your grass type because each time you mow, energy is diverted from root growth to shoot repair. It is also important to mow frequently, removing no more than ⅓ of the grass blade — this keeps the growing point (where all of the grass blades originate) near the soil surface. If you fail to mow, the growing point rises and can be cut off by by mowing. Removing the growing point kills the plant.

Mow the lawn progressively taller up to and through mid-summer to prepare for drought periods.

Leave grass clippings on your lawn. Grass clippings do not contribute to thatch build up. Instead, they recycle valuable plant nutrients and enhance topsoil structure. Successful grasscycling requires mowing often so that no more than ⅓ of the grass blade length is removed. Small clippings decompose faster and can sift downward through the grass better than long clippings. The grass clippings decompose quickly and can provide up to 25% of your lawn’s fertilizer needs. If mowing is delayed and clippings are too plentiful to leave on the lawn, they are still useful. Mix in shredded leaves to prevent matting and create a good carbon:nitrogen ratio for decomposition. The mix can be composted or used as mulch.

Root competition

Trees and grass compete for water and nutrients. Groundcovers or mulch are better than grass around trees.

Some plants are allelopathic, i.e. they secrete chemicals that actively inhibit the growth of other plants. For example, oaks suppress grasses, while some turfgrasses suppress common species of trees (flowering dogwood, sweetgum) and shrubs (azalea, barberry, forsythia, yew).

Weeds

- Turfgrass Weed Identification

- Weed Control in Home Lawns

- Earth-wise guide to products — Toxicity ratings

Pre-emergent

Warm-season annual grasses (crabgrass, goosegrass, foxtail, etc.) and broadleaf weeds are highly competitive with cool-season grasses. A pre-emergent herbicide can be effective, but only if applied before weeds emerge.

Because weed germination depends on soil temperature and varies from year to year, it is best to use natural cues or thermometer readings rather than a specific date for application.

Be sure to water in the product. Most products require at least ¼″ of water within 48 hours of application or they will begin to decompose from sun exposure. Don’t aerate your lawn or you will disturb the barrier that you have just created.

- How to Maximize Preemergence Herbicide Performance for Summer Annual Weeds

- Preemergent Control for Summer Annual Weeds in Lawn and Turf

- Pre-emergent weed control

links

Calendars

Ecofriendly Care